A Holy Week Pilgrimage at the National Gallery London: Good Friday

King David, Isaiah, and the paintings tell the story today

“My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me? Why are You so far from helping Me?…

All those who see Me ridicule Me…

They shoot out the lip, they shake the head, saying, ‘He trusted in the LORD, let Him rescue Him, let Him deliver Him, since He delights in Him!’

I am poured out like water, and all My bones are out of joint; My heart is like wax; it has melted within Me

For dogs have surrounded Me; the congregation of the wicked has enclosed Me. They pierced My hands and My feet;

I can count all My bones…

They divide My garments among them, and for my clothing they cast lots…

All the ends of the world shall remember and turn to the LORD, and all the families of the nations shall worship before You.

For the kingdom is the LORD’s,

And He rules over the nations.”

Psalm 22:1, 7-8, 14, 16, 17a, 18, 27-28

“They also gave me gall for my food, and for my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink.”

Psalm 69:21

“He guards all His bones; not one of them is broken.”

Psalm 34:20

“Into Your hand I commit my spirit; You have redeemed me, O LORD God of truth.”

Psalm 31:5

“…His visage was marred more than any man, and His form more than the sons of men.

He is despised and rejected by men, a Man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.

And we hid, as it were, our faces from Him; He was despised and we did not esteem Him.

Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed Him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted.

But He was wounded for our transgressions,

He was bruised for our iniquities;

The chastisement for our peace was upon Him,

And by His stripes we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray; and the LORD has laid on Him the iniquity of us all.

He was oppressed and He was afflicted, yet He opened not His mouth;

He was led as a lamb to the slaughter,

And as a sheep before its shearers is silent, so He opened not His mouth.

…For the transgressions of My people He was stricken.

…Yet it pleased the LORD to bruise Him; He has put Him to grief.

He shall see the labor of His soul, and be satisfied. By His knowledge My righteous Servant shall justify many, for He shall bear their iniquities.”

Isaiah 52: 14b; 53:3-7, 8b, 10a, 11

Representations of the Road to Calvary/Golgotha and the Crucifixion at the National Gallery London

Today will be a little different. I’d like King David, Isaiah, and today’s paintings to tell the story of Jesus’s sacrifice for us today. I’ve included descriptions from the National Gallery website on each of the pieces to hopefully answer questions that may arise and also provide important context.

Raphael gave us two of the seven paintings we’ll see today and, interestingly, all but one was painted on wood, either with oil paints or egg tempera.

(The footnotes have links to each painting, where you can see details from each work up close, zooming in, if you choose, to see brushstrokes and facial expressions much more closely.)

The Procession to Calvary by Raphael (c.1504-5). Oil on poplar.

“This is one of three scenes from the predella of Raphael’s Colonna Altarpiece, painted for the convent of S. Antonio da Padua in Perugia and named after the Colonna family in Rome who once owned it.

The Procession to Calvary was the central scene of the predella, positioned below the main panel of the altarpiece. Christ looks to us as he carries the Cross, escorted by five foot soldiers, one of whom drags him by a rope round his waist. Simon of Cyrene, behind Christ, helps him bear the weight of the Cross. The Virgin Mary, in dark robes at the far left, is supported by the Three Marys and accompanied by Saint John the Evangelist, who wrings his hands in grief. The three distinct groups of the procession are linked together by a pattern of repeated colour and by the figures who look back over their shoulders at the groups behind.

The Procession to Calvary was originally flanked on the left by The Agony in the Garden (Metropolitan Museum, New York), and on the right by the Pietà (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). The scenes were originally painted on a single plank of wood that was cut into three when the predella was sold.

The predella scenes demonstrate Raphael’s growing talent for narrative and for drawing out a poignant human dimension in biblical stories.”1

Christ Crucified by Antonello da Messina (c. 1475). Oil on wood.

“Christ’s body hangs limply on the Cross, his head bowed and his eyes closed. A trickle of congealing blood seeps from the wound at his right rib. Just beyond the Cross, in the distance, we can see the figures of the Three Marys, Christ’s female followers, on their way home, leaving only the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist to support Christ in his final moments.

Mary – whose figure is the best preserved part of the picture, the surface of which is badly abraded (rubbed) – kneels before the Cross. Resting her hands on her knees, palms down and eyes closed, her whole body seems to be sinking into the ground: she is heavy with grief, absorbed in her pain. John, on the other hand, looks up at Christ, his arms outstretched in frustration or disbelief.

Christ’s body is set against the backdrop of the sky; he no longer occupies the same physical terrain as Mary and John. Antonello has composed the picture with a low viewpoint so that we feel as though we are looking up at Christ, in the same way we might look up at a Crucifix placed upon an altar. This association is a reminder that Christ’s death was, for Christians, part of God’s plan, and that it would come to be celebrated by the Christian Church as an act of salvation.

When this picture was acquired by the National Gallery in 1884 it was framed in the shape of a narrow arch – a section had been added to the top and the upper corners had been removed. It was immediately restored to its original rectangular shape – the shape of the artist’s other Crucifixions – and the cartellino inscribed with Antonello’s signature and the date he made the painting, once on the reverse of the panel, was moved to the bottom of the picture and protected by two strips of wood on either side, added at the same time.

It was not unusual for Antonello to sign and date his pictures in this way.”2

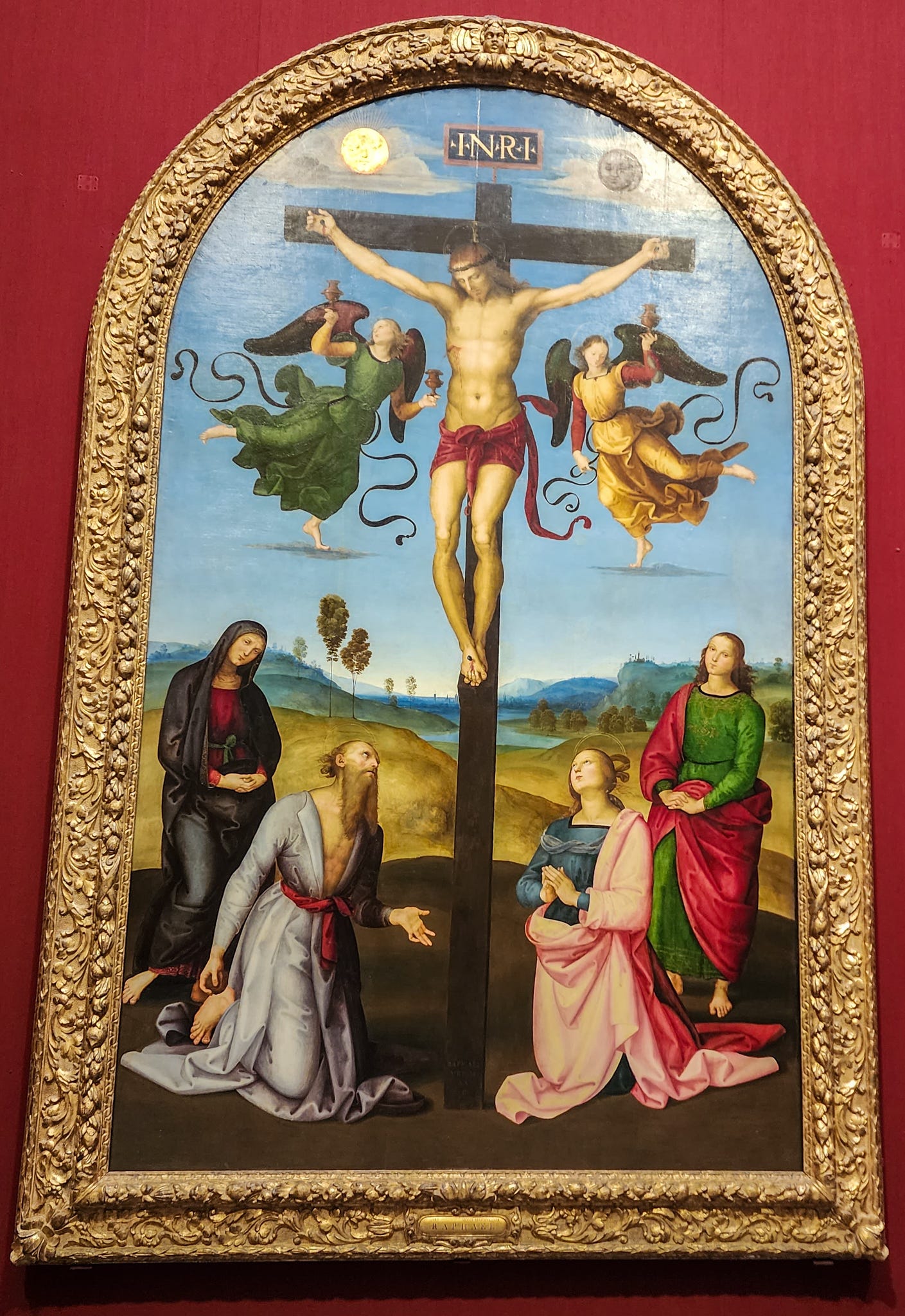

The Mond Crucifixion by Raphael (c. 1502-3). Oil on poplar.

“This altarpiece, one of Raphael’s earliest works, is known as the ‘Mond Crucifixion’ after Dr Ludwig Mond (1839–1909) who bequeathed it to the National Gallery in 1924.

Christ’s body hangs from the Cross, which is surmounted with the inscription ‘I.N.R.I.’, which stands for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum (‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’). Two angels with scrolling ribbons at their waists balance on delicate slivers of cloud on either side of Christ. They catch the blood flowing from his wounds in golden chalices. The inclusion of the chalices is fitting as Gavari left money in his early wills to furnish every chapel he endowed with new chalices.

The Cross, on the brown foreground, is set against a view of the Umbrian landscape. The sun and moon are both visible in the sky, marking the eclipse that coincided with Christ’s death. Raphael used silver leaf for the moon and gold leaf for the sun. Saint Jerome and Mary Magdalene are at the foot of the Cross gazing up at Christ’s body with reverence and pity, providing an example for worshippers viewing the painting. The Virgin Mary, dressed in purplish black to denote mourning, stands to the left of the Cross and John the Evangelist stands to the right. They both look towards the viewer and wring their hands in grief.

Saint Jerome was not present at the Crucifixion but is included in this scene because the chapel [where this painting was to hang] was dedicated to him. He gestures to the Cross and holds the stone with which he beat his breast while living as a hermit in the wilderness.

Gavari himself may have chosen to dedicate the altar to Saint Jerome as he also named his first-born son Girolamo (Jerome in Italian).

The altarpiece is strongly influenced by Perugino, the leading artist in central Italy at the time, with whom Raphael developed a close artistic relationship while living in Perugia. The overall design is based on several versions of the crucified Christ in a landscape painted by Perugino in the late 1480s and 1490s, and is especially similar to his altarpiece of the Crucifixion for the convent of S. Francesco al Monte in Perugia, commissioned 1502 and completed 1506. In that painting angels with fluttering ribbons hold chalices to catch the blood from Christ’s wounds, the Virgin and the Evangelist are almost identical to Raphael’s and Mary Magdalene is in the same pose in reverse on the other side of the Cross. It’s likely that Raphael saw Perugino’s works in his workshop in Perugia before they were unveiled. As well as adopting the sweet, small-featured oval faces and stylised hand gestures of Perugino’s figures, Raphael took the principles of symmetry, harmony and clarity of composition from Perugino’s works. However, Raphael adapted these, giving them greater softness and sophistication. Here, however, it is not entirely clear who copied whose work.

Raphael may have used a ruler and compass to incise the outline of the Crucifix, and compasses to incise the sun and moon. The way he left unpainted spaces for the figures and made no revisions or changes while painting suggests that he was working from a carefully prepared design in a detailed drawing. During this period Raphael frequently used dark hatched brushstrokes to reinforce areas of shadow – a technique derived from Perugino – which is particularly noticeable here in the drape [of the clothing]. Raphael also used his hands and fingers to blot and model the wet surface paint. His fingerprints and palm prints are visible in the shadows of the heads, especially in Christ’s hair, face and beard.

Raphael scratched through the brown paint at the foot of the Cross to a layer of silver leaf beneath to sign the painting: RAPHAEL / VRBIN / AS / .P.[INXIT] (‘Raphael of Urbino painted this’). Vasari famously commented that if Raphael had not signed the painting, no one would have believed that he and not Perugino had painted it.”3

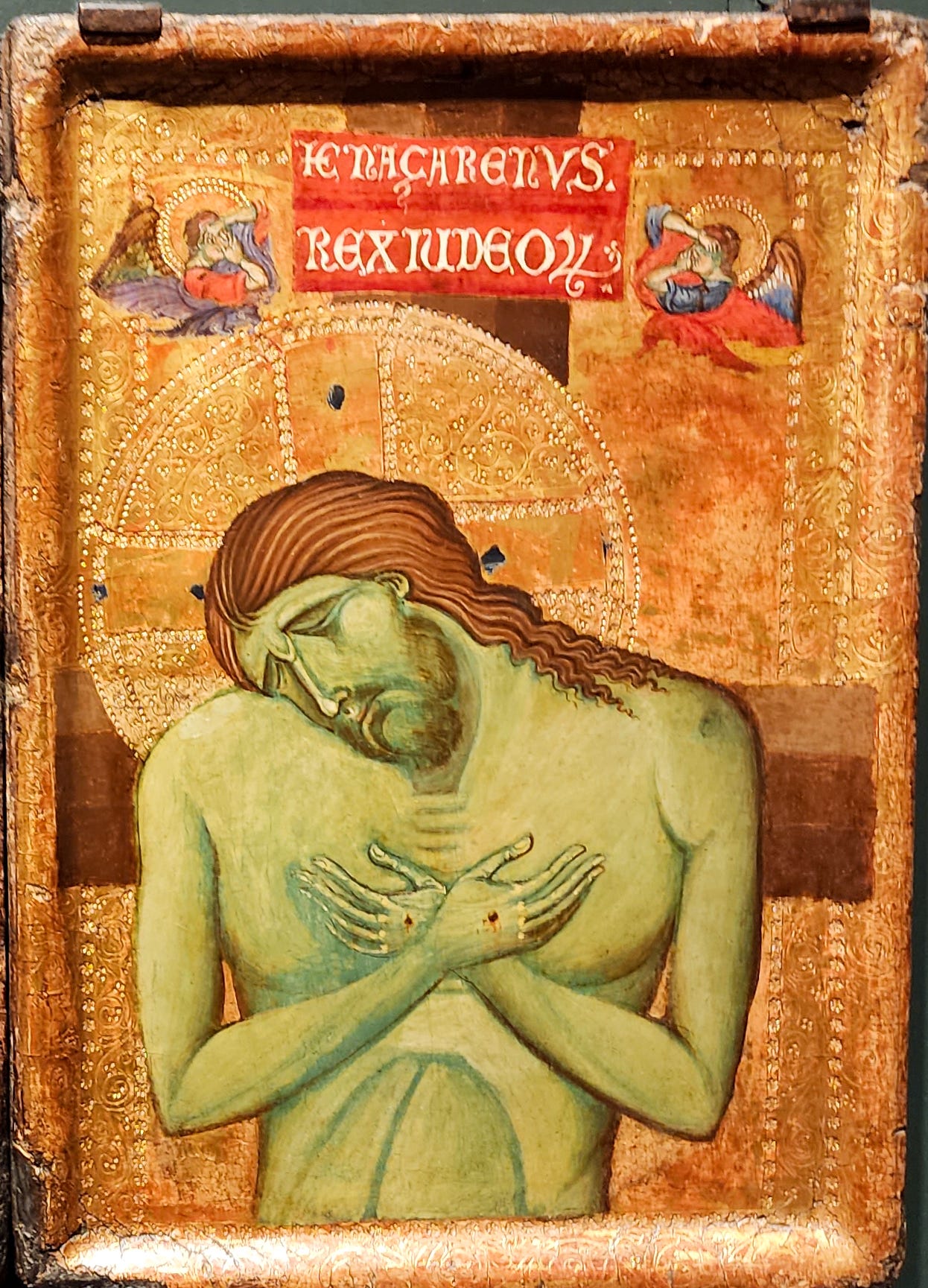

Man of Sorrows by Master of the Borgo Crucifix (c. 1255-60). Egg tempera on poplar.

“Christ is shown just after his death at the Crucifixion, though the Cross behind him is mostly obscured by his large halo. We can see bloody wounds on the backs of his hands, caused by the nails that secured him to the Cross. The holes are brown while the blood dripping from them is bright red, and Christ’s skin has the green tone of a corpse. The inscription at the top of the Cross is in Latin and means ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’; according to the Gospels it was nailed there to mock Christ (John 19:19). Two angels in the upper corners cover their eyes in despair, emphasizing the horror of the sight and provoking the same reaction from the viewer.

The image of the dead Christ shown as a half-length figure with head drooping and arms crossed like this is called the Man of Sorrows. Its origins lie in Byzantine painting (the art of the Eastern Christian empire) but it became very popular in the west in the thirteenth century. The earliest Italian versions of it can be found in manuscript illuminations dating to the second half of the thirteenth century. The Man of Sorrows was popular with the Franciscan Order as they were devoted to the contemplation of Christ’s suffering and wounds.

Cleaning the picture revealed that the Cross had been painted with three tones of brown, which might represent the three different trees from which it was thought to be made: fir, palm and cypress, according to the writer Gregory of Viterbo. The three types of wood were interpreted as symbolising the Trinity.”4

The Vision of Saint Eustace by Pisanello (c. 1438-42). Egg tempera on wood.

“We are looking at a miraculous event. An elegantly dressed huntsman has been stopped in this tracks by an apparition: a large stag with a Crucifix between its antlers. This is Saint Eustace, whose story was told in the Golden Legend, the famous medieval collection of saints‘ lives. A Roman soldier named Placidus was out hunting when he had a vision of a stag with Christ on a shining cross between its antlers. He converted to Christianity at once and changed his name to Eustace.

He doesn’t look like a Roman soldier here, though. Instead Pisanello has depicted an Italian prince, in a fantastic blue hat, out hunting with his hounds. We do not know who this painting was for, but its small size suggests it was for the private enjoyment of an aristocrat. Although he was rarely shown in Italian art, Saint Eustace personified the ideals of the medieval knightly class, for whom hunting was not just a hobby but an enormously important activity. It was seen both as a metaphor for the soul’s search for God and as a virtuous activity which kept men busy – and therefore out of temptation’s way. Most importantly it was the primary training for war, which was aristocracy’s most important function.

Pisanello was especially famous for his ability to show animals. The huge number of his surviving drawings include various studies for the creatures in this painting, some taken from model books, some taken from earlier artists and some from live and dead animals. This painting is full not just of various dogs – some seemingly taken from the lavishly illustrated hunting treatises which were very popular in the fifteenth century – but also birds, a hare and even a bear; all are amazingly lifelike. He paid meticulous attention to detail, comparable to that of contemporary Netherlandish artists such as Jan van Eyck. Look closely and you can see the spiked wheels on the saint’s long rowel spurs and the way the horse’s shoes turn up at the ends to give extra grip on wet ground.

Sadly this painting has suffered considerably from deliberate damage, from changes in the pigments and from restoration. It was once taller and had a less claustrophobic feel. Many of the colours have darkened, obscuring details, and the surface is worn down and has been extensively retouched. The saint’s clothes and many of the animals have been repainted – like the horse, which was originally whitish-grey but has been darkened by retouching. But you can get a sense of the painting’s original quality from the flowers and foliage around horse, which are still in good condition.”5

The Vision of Father Simón by Francisco Ribalta (c.1612). Oil on canvas.

“Francisco Gerónimo Simón (1578–1612) was a priest of the parish church of San Andrés in Valencia. He led an ascetic life and was renowned for his piety and charity. In 1612, the year of his death, Father Simón had a miraculous vision: here he is shown kneeling in front of the towering figure of Christ carrying the Cross, tears streaming down his face, as he reaches out to embrace him. The figure of Christ is very three-dimensional and recalls the polychrome sculptures of the Passion which were carried through the streets during Easter week processions. Christ is followed by a crowd of trumpeting Roman soldiers, Saint John the Evangelist and the Virgin. The soldiers appear squashed and only part of the Virgin is visible now because the painting has been reduced along both vertical sides, and probably along the top. The scene may be set in the Calle de los Caballeros, the street in Valencia where Father Simón is reputed to have had his vision and along which condemned criminals were led to their execution. A tower and church portal can be seen in the distance, with a carriage and small figures going about their daily duties, seemingly ignorant of what is happening in the foreground.

Ribalta’s signature is placed prominently on a cartellino (or paper) lying at Christ’s feet. The picture is dated 1612, the year of Father Simón’s vision and death. A period of fervent devotion followed Father Simón’s death, until his cult was banned in 1619 following a failed attempt to have him officially declared a saint. Certain religious orders, such as the Franciscans and Dominicans, were against venerating Father Simón and images of him were purposely destroyed. This is one of the few remaining large-scale paintings in which he appears: Father Simón’s pale face resembles a true effigy and Ribalta may have seen the priest’s corpse since he was living in Valencia at the time of his death.”6

The Crucifixion by Jacopo di Cione (c. 1369-70). Egg tempera on wood.

“This picture is unusual in Italian painting of this period in showing so much detail from the Gospel accounts of Christ’s crucifixion in one relatively small panel. Such images were usually reserved for large wall paintings. Christ is shown on the Cross between the two thieves who were crucified with him. On the right is the thief who, according to the Bible, mocked Christ. He is tormented by two devils – they hold a brazier, representing hell, over his head. On the left is ‘the good thief’, shown with a halo, who believed in Christ; two angels take his soul, represented as a small baby, to heaven. Christ’s blood is gathered in chalices by angels. One man raises a stick with a vinegar-soaked sponge intended to quench Christ’s thirst, an incident mentioned in all the Gospels apart from Luke.

Between the crosses, Roman soldiers on horseback guard the site, their spears raised. One of them, to the right of Christ [nearest the cross, dressed in yellow], has a blue polygonal halo. He is probably the centurion mentioned in the Gospel of Luke who recognised Christ as the Son of God.

In the foreground a vast crowd is gathered. To the left, soldiers draw straws for Christ’s clothes, as mentioned in the Gospel of John; others cluster at the far right, behind a group of priests or Pharisees. The central group shows the Virgin Mary collapsing in grief and supported by Saint Mary Magdalene, recognisable by her red robes and long red hair. Saint John the Evangelist stands slightly apart from them, raising his hand to his face in grief.

Saints Benedict and Bernard, the founders of the Cistercian Order, flank the Virgin and Child in the roundels below the main scene. The prominent position of women in the scene – particularly Mary Magdalene – and the inclusion of two female saints in the roundels indicates that the original location may have been a nunnery. This was possibly Santa Maria Maddalena di Cestello, the Cistercian nunnery dedicated to Mary Magdalene in Florence.”7

Today’s Scripture Readings (in addition to the earlier prophetic passages):

Matthew 27:32-56

Mark 15:20-41

Luke 23:26-49

John 19:16b-30

IT IS FINISHED!

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jacopo-di-cione-the-crucifixion

*Notes from the information card adjacent to the painting

Photos of the above National Gallery paintings ©Renate Flynn.

Wow, Renate! You have done exceptional work relating the Passion of Christ through this fine selection of historical pictures and your voice. I am once again reading out loud to my husband as we travel from Georgia to Virginia. We started at the SeaTac Airport, coincidentally the last place we were when you were writing Dec 2024 - Jan 2025. I need to go back and read more. The unfathomable humility of Christ juxtaposed with the power of God is in deed almighty for pulling down strongholds and He did it! -- all for us! Like He said, and you reiterated, It is finished! Thank you, Jesus, thank you Father God. Thank you Renate.

Again, I can tell you took great care in creating this post.

To see these works of art and read their descriptions was really interesting. You’ve compiled a vivid retelling! I also find the way the artists chose to depict these historical scenes interesting. Obviously, most of these works reflect the time periods in which they were created. It gives a glimpse into life at that time period as well.

It’s Easter Eve—happy Saturday!